After being sexually assaulted, author and journalist Jennifer Neal thought her body might never recover. Then she began hiking and discovered power in the pain, fear and focus of moving through rocky terrain.

Finding my body through the wilderness

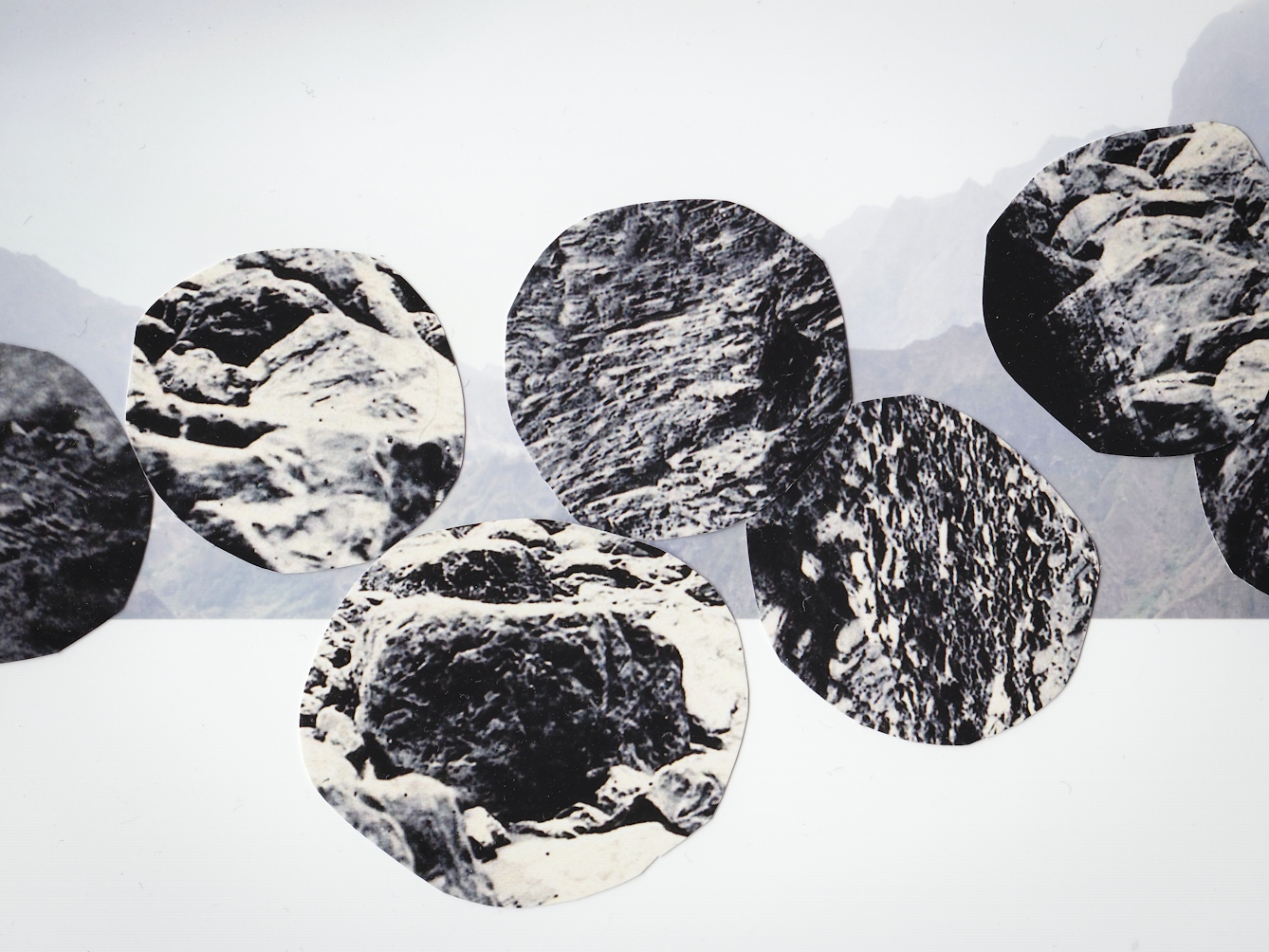

Words by Jennifer Nealartwork by Faye Helleraverage reading time 6 minutes

- Article

The bus driver warned us of heavy winds before dropping us off at the base of Kjerag. “If you fall and break something, call the emergency services line – but do it before six o’clock, because that’s when they go home.”

I had already ascended Preikestolen, the scenic cliff that towers 600 metres over Norway’s Lysefjorden. But Kjerag was different. The wide rock expanse arced from the tips of my hiking boots to the top of the fossil-coloured sky – grey, rock, grey again, as bare and alien as the surface of another planet.

It didn’t have a well-beaten path or loosely formed stairs. The first ascent was a painstaking near-vertical climb where the only thing to grip was a chain bolted into the granite face. If I hurt myself, I would need to be evacuated by helicopter. I had spent the early hours of the morning doing stretches and warming up my already sore joints so that that wouldn’t be necessary... but even then, I could never be sure.

It seems odd that finding my way back to my body has meant navigating through multiple kinds of wilderness. But then again, that’s how it was taken from me to begin with.

Maybe it makes perfect sense.

A body

For years, I moved around in a shadow instead of a body. I didn’t want my body. I didn’t even want to say the words “my body” because that insinuated a sense of ownership or responsibility over what had happened. When I was young, its job had been to bring me pleasure, or at least the illusion of pleasure that we later recognise as youthful abandon and enthusiasm. But I withdrew from almost every shared intimacy.

I had acquired all the aches and pains of a body that had undertaken the serious task of growing old without the warm memories to show for it. It had only been responsible for the greatest pain of my life. I willed myself to detach from it, numbing limbs, organs and electrical pathways. Many mornings I’d wake up, look at my arms, legs, and toes, and think, “Oh, you’re still here?” as if greeting a lover who had overstayed their welcome.

Different therapists recommended different physical exercises. Weights classes. Aerobics classes. Bodypump. I did lots and lots of Bodypump. When I sat down with one plain-faced man, he asked me why I had decided to try therapy again.

“I was raped,” I said.

“Well, there’s nothing we can do about that.” He didn’t even look me in the eye before he began scribbling on his notepad. “So let’s focus on your diet. Eating lots of fruits and vegetables will make you feel better.”

Reader: Eating fruits and vegetables didn’t make me feel better.

“For years, I moved around in a shadow instead of a body. I didn’t want my body.”

A fortress

On my way home from the therapist – whose office I would never visit again – I took a long walk. On long walks, my senses weren’t focused on pain; they were focused on tall buildings, smells from new restaurants, green parks and swooping birds as I went from one place to another.

Physical pain could be a trigger that I had to persuade myself to disregard. It was a reminder of how easily my body could be used against me, and the soreness that followed for days after only reminded me of how weak my body was. A single aching joint became a rapid, destructive descent into a psychosomatic response where everything bent, tore and bruised. After all, the only thing worse than having a body was having a weak one.

I lived in a crowded city, constantly negotiating the physical space of others. Hiking offered me the pursuit of space. But it also became an opportunity to learn that a delicate balance between physical pleasure and physical pain could actually exist – if only I was willing to learn how to move towards something instead of run away.

Hiking didn’t isolate major muscle groups from minor muscle groups in a series of static exercises. It demanded my complete devotion. It activated segments in my fingers, in my toes, in the complex muscles that surround my hip joints, and in my clenched jaw.

My first solo hike was Walsh’s Pyramid in Northern Queensland. It was 39° C at the early onset of Australian summer, and weeks of Bodypump classes had given me a false sense of what it took to conquer the unshaded peak covered in king brown snakes, kookaburras and geckos.

It was meant to take three to four hours. It took me six and a half. I rolled my ankle on the way down, gripping rocks and crawling through brush as rain clouds rolled in. With only a camel bag of water, and almost no experience in the Australian bush, I now realise it was just as much a hike as a death wish.

But even then, while icing a swollen ankle the size of an orange in my rental car as I devoured a box of muesli bars, I woke to the possibility that my body could be many things – an adversary. Or a fortress.

“I resolved that every time I stood in front of a mountain or a trail, I would see myself as someone becoming part of something bigger.”

A climb

I had never even thought to look at my body in that way – and when I did, those two words felt less like a source of shame and more like a source of pride. Strength necessitated pain, and hiking would help me to wield it, to glorify a body that had survived so much of it. Survivors know a lot about shame, but not much about pride.

I resolved that every time I stood in front of a mountain or a trail, I would see myself as someone becoming part of something bigger. I would fuse myself to that place and allow myself to feel all the parts of my body that I’d spent years trying to forget were part of me. All of me.

If I was an extension of the steep descent into the Vale do Paul in Cape Verde, I wouldn’t fall into it. If I was an extension of the snow-covered surface of Gaisberg, then I wouldn’t slip down its icy surface. Hiking isn’t a spiritual communion with nature – though that certainly does happen. I learned to respect the strength of it, and that helped me recognise the courage in myself.

I would fuse myself to that place and allow myself to feel all the parts of my body that I’d spent years trying to forget were part of me.

My ascent up Kjerag wasn’t a hike – it was a climb. A half day of deep hip lunges up and down a near-vertical cliff, through snow-laden crevices, against icy winds. An exhaustive series of calculations of finger against rock against boot against balance. When I finally reached the summit, I envisioned my body as an extension of the granite surface I traversed. I wasn’t soft and vulnerable. I was hard and impenetrable. I could break things, but I could not be broken.

And when I stood on the boulder wedged between two cliffs more than a thousand metres above a seamless current, I felt as invincible as the rock beneath my feet – even if my kneecaps shook in their sockets.

About the contributors

Jennifer Neal

Jennifer Neal is an author, journalist, musician, visual artist and occasional stand-up comedian based in Berlin. Her work has appeared in Gay Magazine, Atlas Obscura, The Willowherb Review and Playboy, among many others. She is a 2021 MacDowell Fellow, and her first novel, ’Notes on Her Colour’, will be published in May 2023 with Catapult (US) and Penguin Random House Australia. Her non-fiction book, ‘My Pisces Heart’, will be published in autumn 2024 with Catapult (US).

Faye Heller

Faye Heller studied for her MA in Fine Art at the Slade School, University College London, UK and is a qualified teacher. She has been making artwork for over 25 years and her work was shown at the Tate Modern on a late night for the Dora Maar exhibition in 2020. Using handmade photomontage and collage, she combines portraiture with the natural and man-made landscape, exploring the psychological and environmental, and evoking layers of time, landscape, places and encounters.