Author Rowan Hisayo Buchanan didn’t think she was a dog person – but a longing for a little wildness in her domesticated life changed that. Dogs, she found, help us understand the borders between nature and culture, as well as how animals can teach us something of being human.

A little wildness

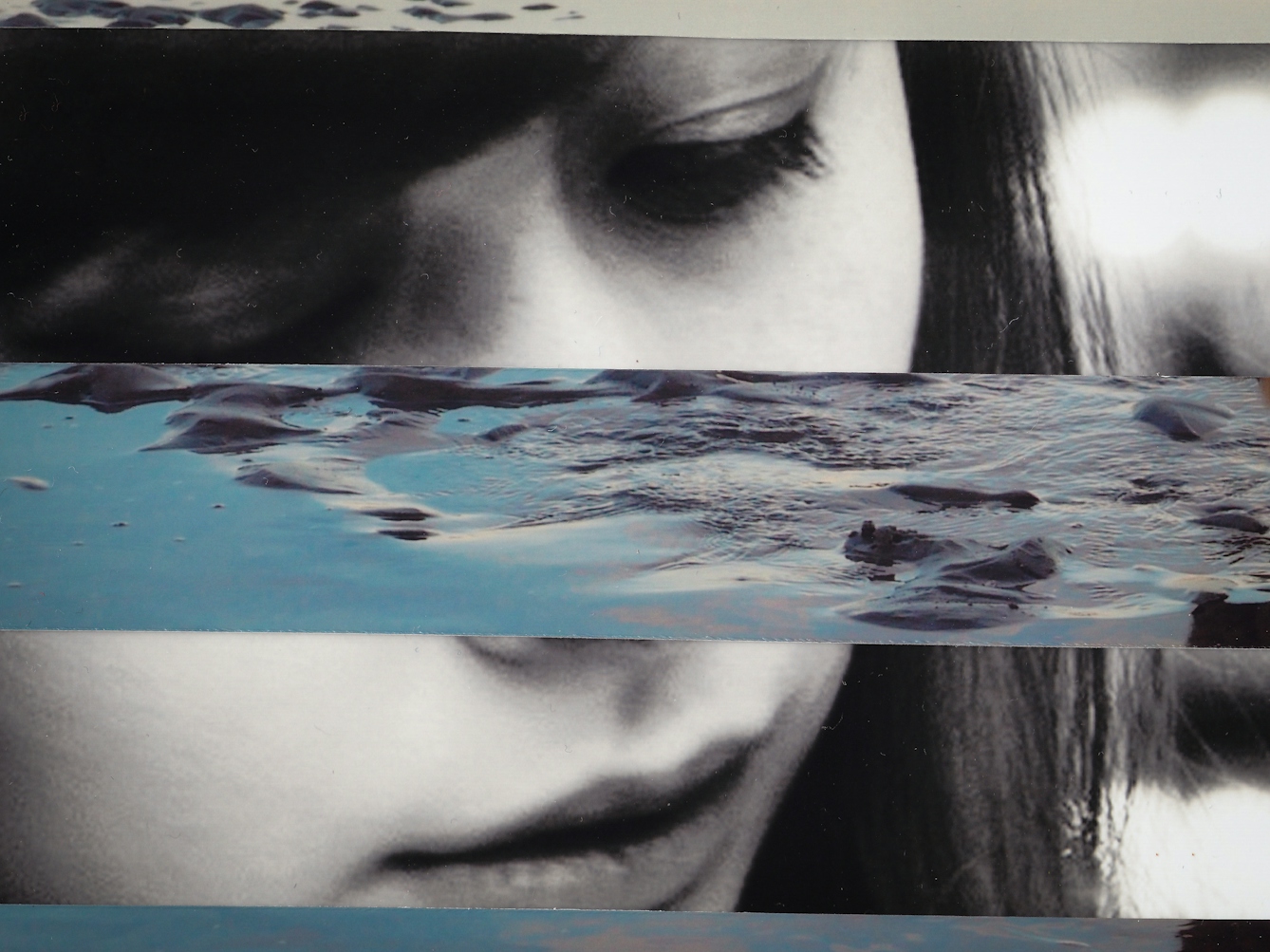

Words by Rowan Hisayo Buchananartwork by Faye Helleraverage reading time 7 minutes

- Article

I did not consider myself a dog person. But for two years, each time I saw a dog, I was squeezed by longing. It started almost without my noticing it. In my second novel there is a large mutt. As I wrote, I found myself watching other people’s dogs. I told myself it was the writer’s eye. But eventually I had to admit the desire was so strong it felt physical.

My mother said I wanted a child. I told her that babies just looked like fragile humans to me; I wanted a dog. She argued if I had a baby that one day it could grow up and read – an appeal to me as writer, a lover of books, a collector of stories. Still, I got the dog.

In the 12th century, in a kiln in northern China, someone made a dog. The dog was small. Its tail curved up. Its ears were pointed. We think it was toy or funeral object. A dog is a good companion for a child or for someone slipping off this earth. This dog was not for nobility or royalty. They made it for an ordinary person. It is small enough to be enclosed in an ordinary hand.

The desire for a dog is an ordinary desire – one so old it hardly seems worth commenting on. And yet I have found myself struggling to explain what a dog might offer that a child or a book might not.

Every day I see dogs: mastiffs with sagging jaws, pig-tailed pugs, bat-eared Frenchies, all the poodles. And of course, my own – a Tibetan spaniel.

The name is deceptive. She was born in Norfolk and is not related to a cocker, springer, or King Charles. She is simply the descendant of some temple dogs that someone thought looked a bit like a spaniel. She is a brown that has been called fawn, prairie, caramel, wild dog and gold. She weighs 4.5 kg – about the same as a large cat or about 40 bananas.

Michael Pollan in ‘The Botany of Desire’ notes, “There are fifty million dogs in America today, only ten thousand wolves.” Britain, where I live, is wolfless. Pollan argues that domesticating animals and plants is to both their benefit and ours. We are our dogs’ chefs, servants, matchmakers, home builders.

“My mother said I wanted a child. I told her that babies just looked like fragile humans to me; I wanted a dog.”

What I don’t understand is why I need her. Why do I boil rice to mix with her kibble? Why do I interrupt my work to pace up and down the canal by her side? Why do I turn down any invitation that might stop me from caring for her?

My dog is classed as a utility breed. But she is not useful in any obvious sense of the word. She is too small to defend me. She cannot swim or pull a sled. She does not kill rats or retrieve birds. Perhaps what I needed was just to be walked. Many winter days the earth spun and I stayed inside. I had work to do. I had food prepared. There was no reason to leave my walls. I needed a reason to see the sky.

Now I have the dog, I stand under skies, grey, blue and black. Though often I am looking down, not up, watching as my dog lifts her nose to the sweet-sour smell of marijuana emanating from a group of teenage boys.

A worry

They say that people look like their dogs. I wonder if this is because people mould their dogs or if we are drawn to the thing that resembles us. There are big-dog people and small-dog people. Huskies, Alsatians, Eurasiers, deerhounds, Malamutes, Samoyeds are strong-legged, powerful-jawed. There is a gravitas to big dogs – a proximity to wolves. They may be gentle, but there is, in their proportions, the story of wilder time.

I worry there is something undignified about being a small-dog person. I have worked for years to seem serious and intellectual. Why would I add a small dog?

Chekhov wrote a story called ‘Дама с собачкой’. The title is translated in various ways. Sometimes it is ‘The Lady with the Dog’, sometimes it is ‘The Lady with the Little Dog’ or ‘The Lady with the Toy Dog’. A Russian speaker told me that собачкой signifies both smallness and a cuteness. If Chekhov had meant simply ‘dog’, he would have used собака.

The subject of the story is not the dog. It appears in the very beginning and then glancingly in the middle. It is never named. It seems mainly to be a symbol of its mistress’s vulnerability and innocence. Did some secret vulnerability reveal itself when I chose this pup, the runt of her litter?

Hopes and fears

Study after study has found that pet animals reduce depression in humans. I once dated a man so slumped by depression that he stopped speaking to any of his friends. But if I pointed at a hound and said, “Look, puppy!” a smile cut open his face. Back in 1859 Florence Nightingale recommended that “a small pet animal is often an excellent companion for the sick”.

“My dog is classed as a utility breed. But she is not useful in any obvious sense of the word. Perhaps what I needed was just to be walked.”

I recently stumbled on a study about canine-assisted reading. It claimed that: “Dogs, in particular, are thought to provide a non-threatening yet socially supportive and interactive audience for children practising their reading skills.” Children in a Florida school read to a dog named Hope.

Did I think the dog would cure some brokenness? My partner says I seem less anxious since we got her. Yet she has given me new fears. For two months, all her food made her ill. Her small body heaved bile onto the floor. There are chicken bones all over the city, each one a potential splinter for her throat. She too spots threats – suitcases move like alien animals. A billowing tarpaulin might as well be the flank of some giant.

A memory of wolves?

There is a quote from Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s book ‘Le Petit Prince’ – “You become responsible, for ever, for what you have tamed.” To be tame does not just mean to be pliable to human will. A sock or a table or a lampshade are not tame. To be tame is to have the capacity for wildness.

Things my dog tried to destroy while teething:

A rug I’ve had since I was born.

My jumper.

My hair.

Five chair legs.

The door’s threshold.

I wish for her to obey. Yet her ability to disobey distinguishes her as her own creature.

She has learned not to bite, but sometimes when we play, she opens her mouth to show that she could. For a moment, I see her teeth, ridged as mountains, before she wets my hand with her sticky tongue.

Good wolfling, I say. Good wolfling.

For the moment

I turn to the dog lying beside me on the sofa. Her eyes slide open and shut. I began this essay before the pandemic filled our lives. As I write, I wonder, who will care for her if I am sick? As my mother said, dogs can’t read. The news is lost on her. She eats a chew with her eyes closed.

She is not a child, not human, not medicine; only a small wildness who I have let into my home. She yawns and so do I. So for a while we rest our drowsy animal bodies side by side.

About the contributors

Rowan Hisayo Buchanan

Rowan Hisayo Buchanan is the author of ‘Harmless Like You’ – the winner of the Authors’ Club First Novel Award and a Betty Trask Award. It was a New York Times Editors’ Choice and an NPR 2017 Great Read. Her second novel, ‘Starling Days’, was shortlisted for the Costa Novel Award. Her short work has appeared in several places, including Granta, The Atlantic, and NPR’s Selected Shorts. She is the editor of the ‘Go Home!’ anthology.

Faye Heller

Faye Heller studied for her MA in Fine Art at the Slade School, University College London, UK and is a qualified teacher. She has been making artwork for over 25 years and her work was shown at the Tate Modern on a late night for the Dora Maar exhibition in 2020. Using handmade photomontage and collage, she combines portraiture with the natural and man-made landscape, exploring the psychological and environmental, and evoking layers of time, landscape, places and encounters.